It isn't flat.

Perry says he's against progressive taxation and wants a tax code "that you can put on a postcard." But his own plan doesn't eliminate the federal income tax rates. He keeps those rates but adds an alternative flat tax, which you're apparently free to choose or reject. So he seems to want to complicate the federal income tax. You might still be able to write his plan on a postcard, by writing out the 6 tax brackets plus an alternative flat tax. On the other hand, that means the progressive tax could also fit on a postcard.

There's no significant difference between Perry's plan and the current income tax as far as simplicity or length. The real difference is that, as the first link explains, Perry's plan would be a huge tax cut for the rich, which would decrease revenue, which would increase the deficit.

Perry says that reducing tax revenue would be a good thing, since then we'll need to reduce federal spending. "All of these tax cuts will be meaningless if we do not control federal spending." So he seems to subscribe to the "starve the beast" theory. Well, that theory has been tried, and it doesn't work.

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

Rick Perry's "flat tax"

Friday, October 21, 2011

Thursday, October 20, 2011

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

Anderson Cooper's "47 percent" tax lie in the debate

In last night's debate, Anderson Cooper asked this question:

Congresswoman Bachmann, you said in the last debate that everyone should pay something. Does that mean that you would raise taxes on the 47 percent of Americans who currently don’t pay taxes?Greg Sargent says:

I don’t really consider it part of my job here to think about where candidates messed up, especially since a lot of their factually incorrect statements are just playing to their audience, and you sort of have to expect a lot of that. But Anderson Cooper, the CNN moderator, has no excuse: his claim that 47% of American pay no taxes was inexcusable. Just terrible. The correct stat is that 47% of US households don’t pay federal income taxes, which is very different. It’s bad when politicians get basic factual stuff wrong; it’s terrible when CNN does. To me at least, the debate had a clear loser, and it was Anderson Cooper and CNN for that question.

Tuesday, October 18, 2011

Live-blogging CNN's Las Vegas Republican presidential debate

I'll be live-blogging the debate starting soon. There will also be live-blogging on TalkingPointsMemo, National Review, and the New York Times.

Feel free to post any comments about the debate (or the election) in the comments.

[ADDED: Here's the transcript, and here's the video:]

7:58 - This seems to be online only: we see someone warming up the audience, encouraging them to applaud as wildly as possible. He introduces Anderson Cooper (who I walked by on the street the other day). Cooper tells the audience we're going to start with the National Anthem, which he'll sing very quietly because he has a terrible voice. Good, this will give me time to make a salad before the actual debate starts.

8:02 - The opening sequence has majestic music (to conjure up the West), and an announcer gives us a basic run-down of who has what at stake. After summing up Mitt Romney (holding steady in the top tier), Rick Perry ("trying to get back on track after a meteoric rise"), and Herman Cain (surging), the announcer says that Newt Gingrich, Michele Bachmann and Ron Paul are still trying to break through, while Rick Santorum is described as trying to "beat the odds." Santorum fans (if they exist) had to cringe that he was placed in a lower tier than everyone else including Ron Paul.

8:07 - An aggressively masculine rendition of the Star Spangled Banner.

8:08 - Fortunately, this is the second debate in a row with no bells to signal when a candidate's time is up.

8:09 - Everyone is giving an opening statement. Santorum includes a sweet message to his daughter, who had surgery today and is doing fine.

8:10 - In Cain's opening statement, he says he's "a businessman, which means I solve problems for a living." Romney goes next and awkwardly echoes Cain's intro.

8:10 - In his opening statement, Perry forcefully says he's "an authentic conservative, not a conservative of convenience." A heavy-handed swipe at Romney.

As always, I'm writing down quotes on the fly, so they may not be verbatim.

8:14 - Santorum: "Herman's well-meaning." But 84% of Americans will pay more in taxes under Cain's 9/9/9 plan.

8:16 - Cain denies that he's proposing a value added tax. Bachmann insists that he is proposing a VAT. (I recently blogged about this.) The VAT just tricks people into thinking businesses, instead of government, are making them pay more.

8:17 - Perry calls Cain "brother" twice in his answer on why the 9/9/9 plan won't work. [Here's the video, which also shows that he uses a different word for Romney:]

8:19 - Paul makes a crucial, surprisingly overlooked, point: any time you increase spending, you're effectively raising taxes (I would add: especially as long as we're in debt). The taxes will have to go up sooner or later. The fact that we don't experience the tax increases right away doesn't change this fact.

8:21 - So far it's almost all been about 9/9/9. There's a lively exchange between Cain and Romney. Cain says Romney and Perry are "mixing apples and oranges" by equating his proposed federal sales tax with the current state sales taxes. Romney retorts: "I'll have a bushel of apples and oranges, because I'll be paying both taxes."

8:24 - Bachmann says "every American should pay something" in taxes. Well that's good, because that's already true.

8:25 - Perry says he's finally released his economic plan. His plan is to extract our own energy, which would "create 1.2 million jobs." How long a period of time do you think he's referring to? A quarter? A year? Nope. 7 years.

8:29 - Santorum uses his favorite strategy of interrupting another candidate, and Romney responds very sharply, repeatedly saying: "Rick, you've had your chance — let me speak." That might be the most heated moment Romney has had in any of these debates. Santorum eventually announces that Romney's time is up before he's gotten a chance to say one sentence! The audience boos.

8:33 - Romney gets Gingrich to admit that Romney got the idea for his health-care plan's individual mandate from Gingrich and the Heritage Foundation.

8:42 - Perry says "Mitt loses all standing" on illegal immigration because Romney hired an illegal immigrant and knew about it for a year. Once Romney starts answering, Perry uses an uncannily similar strategy to Santorum's, jabbering over Romney for the whole time he's talking. Romney (who's right next to Perry) puts his hand on Perry's shoulder and leaves it there for a long time. Romney: "You have a problem with allowing someone to finish speaking. And I'd suggest that if you want to be President of the United States, you ought to let both people speak." Have Perry and Santorum privately agreed to the same line of attack against Romney — talking over him throughout his whole time — or did Perry spontaneously decide to emulate Santorum? Either way, Perry and Santorum are using a cowardly tactic and creating the impression that they're afraid of letting Americans hear the whole debate.

8:46 - Anderson Cooper asks Cain why he said he supported an electrified fence along the southern border, then said it was a joke, then said he stood by the statement and just didn't want to offend anyone! Cain starts out saying he's finally going to be serious, but he doesn't clarify whether he still supports an electrified fence.

8:52 - I just noticed this is the first debate without Jon Huntsman. [ADDED: He's boycotting Nevada. That'll do him a lot of good.]

8:52 - Perry brings back his attack against Romney for supposedly hiring illegal immigrants. The audience boos very loudly for a long time. Romney says: "We've been down that road sufficiently, and it sounds like the audience agrees with me." Once Romney says that, the audience immediately switches to cheering. That was Perry's big attempt to offset the charges that he himself is soft on illegal immigration, and the attempt failed miserably.

9:01 - I'm adding the "free speech" tag to this post, since the candidates seem to disagree on whether they should all get a chance to speak.

9:11 - Cain stands by his past statement about Occupy Wall Street: that if you're not rich, blame yourself. Ron Paul: "Cain is blaming the victims."

9:21 - Santorum makes a smart statement on the relevance of religion in a presidential race. The candidate's faith has to do with their values, and that's relevant for voters to consider. In contrast, whether the candidate is right or wrong about "the road to salvation" shouldn't be part of the political arena.

9:22 - Gingrich tries to outdo Santorum by saying that the idea that we were "created by a loving God" defines the boundaries of . . . what? (I'm having trouble paraphrasing him because I found this so incoherent.)

9:23 - Perry has been pausing a lot throughout the debate.

9:33 - Paul: "We have enough weapons to blow up the world 20, 25 times."

9:37 - Paul would "cut all foreign aid," which is "taking money from poor people in this country and giving it to rich people in poor countries." He emphasizes that this includes Israel.

9:41 - Gingrich, answering a question by Paul, says that the Iranian "arms for hostages" deal in the '80s was "a terrible mistake."

9:46 - Santorum says Romney in Massachusetts "ran as a liberal, to the left of Ted Kennedy." Romney laughs on cue.

9:48 - Romney: 40% of the jobs created in the last several years in Texas have gone to illegal immigrants. Perry says this is wrong, and adds: "You failed as the governor of Massachusetts." Romney responds that his unemployment rate in Massachusetts was lower than Perry's in Texas during the same time period.

9:49 - Romney: We need "someone who's created jobs, not just watched them being created by others."

9:50 - Cooper asks Cain a dumb question: Should either Romney or Perry be President? "No, I should be President!"

That's all. Now, here's the moment this debate will be remembered for:

Jonah Goldberg says:

I don’t think anyone left the debate more likable than they were when they went in, with the possible exception of Newt.Maybe he was reading Jason (the Commenter)'s Twitter feed:

My scoring of the debates: Cain -1, Romney -2, Perry -5, Bachmann -1, Santorum -2, Newt (my new favorite)Goldberg elaborates:

I thought Perry had his best performance so far, but it was awfully shaky at times and he struck me as unlikable at times. If this had been his first debate, he might still be the frontrunner, albeit with a lot of chatter about how he needs to get better.

Romney still won the debate but I think he finally got bloodied on RomneyCare in a way he hadn’t in the past. He also looked angry and flustered for the first time ever. It might humanize him for some people. Or it might make him look weak.

Cain wilted under the pressure, but didn’t fold. He needs to learn how to talk about 9-9-9 in a granular way without asserting ignorance, laziness or dishonesty on the part of its critics. He remains a mess on foreign policy.

Santorum was the winner on points in almost all of his exchanges but he simply cannot stop sounding whiney, angry or aggrieved. . . . [H]is tone is so unpresidential you want him to stop talking even when he’s winning.

Bachmann’s simply a diminished candidate who thinks saying Obama is a one-term president is an argument for her.

All in all, an exhausting debate.

Sunday, October 16, 2011

Is Herman Cain's 9/9/9 tax plan really a 9/18 plan?

According to an article on the American Enterprise Institute's site:

A [value added tax (VAT)] and a retail sales tax are conceptually equivalent consumption taxes, apart from administrative and compliance issues. The [9/9/9] plan is therefore better described as featuring a 9 percent income tax and an 18 percent consumption tax.That assumes that when Cain says he'll have a "9% business tax," he really means a VAT. I don't know if that's true. The article says it's been "confirmed by the economic analysis circulated by Cain's campaign," but that's pretty vague.

Cain's website says this tax will be on a business's "[g]ross income less all purchases from other U.S. located businesses, all capital investment, and net exports." The Wikipedia entry for "gross receipts tax" (a.k.a. "gross excise tax") says:

A gross receipts tax is similar to a sales tax, but it is levied on the seller of goods or services rather than the consumer.In the last debate, Cain said his 9/9/9 plan is "simple, transparent, efficient, fair, and neutral." Many people have noted that it's hardly "efficient," "fair," or "neutral," but I'm not even convinced that it's "simple" or "transparent."

UPDATE: The Economist has an editorial entitled "Dial 9-9-9 for nonsense," which says:

Mr Cain touts the simplicity of the 9-9-9 plan, but it is anything but simple. Even after reading about it on Mr Cain's campaign site, I'm still not sure I understand it. I thought I knew that the plan proposed 9% income, sales, and corporate tax rates. But the corporate tax is not a simple reduction in the corporate tax rate, as I had thought, but a value-added-tax on "Gross income less all purchases from other U.S. located businesses, all capital investment, and net exports."The Editors of National Review have also come out against the 9/9/9 plan, saying that the corporate tax is really a VAT.

Friday, October 14, 2011

The statistical point that neuroscience papers get wrong half the time

Ben Goldacre explains.

The explanation does take a few dense paragraphs; Goldacre admits his own writing is going to cause some "pain" for readers, and I had to read it twice before I got it. But it's worth it for anyone interested in brain studies.

UPDATE: I posted the article to Metafilter, where a commenter named "valkyryn" takes another shot at explaining it:

Say we've got two samples, A and B. For our sample size and subject matter, if we expose it to chemical X, any detected results need to be above 20 Units (U) to be statistically significant.IN THE COMMENTS: LemmusLemmus illustrates the problem with this graph:

We expose A to X, and we get a result of 30U. That's statistically significant.

We expose B to X, and we get a result of 15U. That isn't statistically significant.

But note that the result for A is less than 20U from the result for B. This means that while we did have a statistically significant finding for A, the difference between A and B is not statistically significant.

This significantly diminishes the value of our findings, as the math only supports a relatively unambitious claim. We want to say that A and B are different, but the math won't let us, as the difference in reaction between A and B is too small. We're left with a relatively uninteresting finding, namely that something seems to happen with A and X, but we aren't sure how much that matters.

Careers tend not to be made out of this kind of finding, and the author is implying that because scientists have an interest in careers, they're making more ambitious claims than their studies actually permit.

LemmusLemmus explains:

The result for condition A is significantly different from zero (i.e., it "is significant"), while the result for condition B is not (the confidence interval for A does not include zero, but the confidence interval for B does). However, the two confidence intervals overlap, which means that the results for conditions A and B are not significantly different from each other.

Thursday, October 13, 2011

Should liberals support the Occupy Wall Street protests?

Nope, argues The New Republic:

At first blush, it would be difficult not to cheer the protesters who have descended on lower Manhattan—and are massing in other cities across the United States—because they have chosen a deserving target. Wall Street should be protested. Its resistance to needed regulations that would stabilize the U.S. economy is shameful. And, insofar as it has long opposed appropriate levels of government spending and taxation, it has helped to create a society that does a deeply flawed job of providing for its most vulnerable, educating its young, and guaranteeing economic opportunity for all.

But, to draw on the old cliché, the enemy of my enemy is not necessarily my friend. Just because liberals are frustrated with Wall Street does not mean that we should automatically find common cause with a group of people who are protesting Wall Street. Indeed, one of the first obligations of liberalism is skepticism—of governments, of arguments, and of movements. . . .

One of the core differences between liberals and radicals is that liberals are capitalists. They believe in a capitalism that is democratically regulated—that seeks to level an unfair economic playing field so that all citizens have the freedom to make what they want of their lives. But these are not the principles we are hearing from the protesters. Instead, we are hearing calls for the upending of capitalism entirely. American capitalism may be flawed, but it is not, as Slavoj Zizek implied in a speech to the protesters, the equivalent of Chinese suppression. “[In] 2011, the Chinese government prohibited on TV and films and in novels all stories that contain alternate reality or time travel,” Zizek declared. “This is a good sign for China. It means that people still dream about alternatives, so you have to prohibit this dream. Here, we don’t think of prohibition. Because the ruling system has even oppressed our capacity to dream. Look at the movies that we see all the time. It’s easy to imagine the end of the world. An asteroid destroying all life and so on. But you cannot imagine the end of capitalism.” This is not a statement of liberal values; moreover, it is a statement that should be deeply offensive to liberals, who do not in any way seek the end of capitalism. . . .

And it is just not the protesters’ apparent allergy to capitalism and suspicion of normal democratic politics that should raise concerns. It is also their temperament. The protests have made a big deal of the fact that they arrive at their decisions through a deliberative process. But all their talk of “general assemblies” and “communiqués” and “consensus” has an air of group-think about it that is, or should be, troubling to liberals. “We speak as one,” Occupy Wall Street stated in its first communiqué, from September 19. “All of our decisions, from our choices to march on Wall Street to our decision to camp at One Liberty Plaza were decided through a consensus process by the group, for the group.” The air of group-think is only heightened by a technique called the “human microphone” that has become something of a signature for the protesters. When someone speaks, he or she pauses every few words and the crowd repeats what the person has just said in unison. The idea was apparently logistical—to project speeches across a wide area—but the effect when captured on video is genuinely creepy.

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

Why it's better to fund solar energy with venture capital than with government loans

A compelling argument by Megan McArdle.

The whole post is worth reading, but here's a sample:

A number of people have claimed that the government had to make these loans because they're "too risky" or "too big" for the private sector, forcing the government to act as a VC firm. That riskiness means that yes, a non-insubstantial number of the loans will fail.

But this doesn't really make any sense. The private sector doesn't have any trouble dealing with risky ventures; it simply prices the capital accordingly, demanding high interest rates, or a larger equity chunk, in exchange for money. . . .

[A]t the company level, there's no difference between an optimal market outcome, and an optimal social outcome (from the DOE's point of view); both investors and society benefit if more solar cells are sold. If the solar cells are unlikely to be sold to many people, than the loan guarantee is not a good idea — it will not foster much environmental benefit. If the solar cells are likely to be sold to many people, than the loan guarantee should not be needed; private investors should be easily found to back the manufacturing.

Tuesday, October 11, 2011

Live-blogging the first Republican debate since the rise of Herman Cain

[Here's the complete transcript.]

I'll be live-blogging here, and there's also live-blogging at TalkingPointsMemo and National Review (in the second column of the homepage).

As always, I'll be typing any quotes on the fly without the benefit of a transcript. So they might not be verbatim accurate, but I'll try to keep them as close as possible.

8:00 - The candidates are sitting around a table, for the first time in this race.

8:01 - Also unlike any of the previous debates, this one will be only about the economy. Good.

8:04 - Rick Perry says he'll finally get around to releasing some specific plans.

8:05 - Mitt Romney emphasizes the importance of working with both parties, which he knows how to do based on his experience in a state dominated by the other party.

8:07 - Charlie Rose presses Perry for some specific proposals. He makes some general statements about energy independence, and says he isn't going to lay out his plan tonight. He says it's unfair for Romney to criticize him for not having a specific plan yet: Romney has had 6 years to run for president, while Perry's only been doing it for 8 weeks. [ADDED: How conservative is it of Perry to be complaining that Romney has an unfair advantage because he's worked longer and harder at this?]

8:09 - I like this format. It feels more serious and composed than the podium/standing debates. It's also more dramatic when a candidate looks at another candidate from across the table. So far, I'd say the format is good for Cain, Romney, and Michele Bachmann, and not so great for Perry.

8:12 - Newt Gingrich is very strident on what he considers the corruption of the Federal Reserve. The moderator prompts hearty laughter around the table by saying, "So, Congressman [Ron] Paul, where do you stand on this issue?"

8:15 - Rick Santorum says that in contrast with Cain's "9/9/9" plan, his plan will actually pass in time to respond to the ongoing economic crisis.

8:17 - Thankfully, this debate is free of those annoying bells to signal when the candidates' time is up.

8:19 - Gingrich says Sarah Palin was unfairly attacked for coining the phrase "death panels." He claims that federal government standards on prostate cancer are effectively going to kill men.

8:20 - Bachmann: "President Obama plans for Medicare to collapse, and everyone will be pushed into Obamacare."

8:22 - Huntsman on Cain's "9/9/9" plan: "It's a catchy phrase. I thought it was the price of a pizza when I first heard of it." Huntsman finally pulls off a zinger that works.

8:23 - Cain is on fire as he responds to Huntsman and Santorum: "9/9/9 will pass, and it is not the price of a pizza. And unlike your plans, it starts by throwing out the current tax code. . . . It will pass, because the American people want it to pass." Oh, so the American people want to make the rich richer and the poor poorer?

8:25 - The moderator and Romney spar over whether the moderator's question about a future economic collapse of Europe is a "hypothetical." The moderator says "it's not a hypothetical" because it's about "a very real threat." When did people stop understanding what the word "hypothetical" means?

8:28 - Romney quotes Milton Friedman: "If you took all the economists in America and laid them end to end, it would be a good thing." But Romney has more respect for economists than that.

8:31 - TalkingPointsMemo has a huge headline:

Gingrich Calls For Jailing Sen. Dodd And Rep. FrankActually, he only called for "looking at" jailing Senators Chris Dodd and Barney Frank. [Clarification: Gingrich did at first make a pretty clear statement that we should jail Dodd and Frank, though he said this after the word "if," so he has plausible deniability. Later, he softened his statement to say we should investigate Dodd and Frank.]

8:47 - Bachmann criticizes Cain's "9/9/9" plan for "creating a new revenue stream for Congress." If you turn it upside-down, "the Devil is in the details."

8:49 - Huntsman criticizes Romney for wanting to start a "trade war" with China.

8:51 - Perry seems to come out against the very idea of enacting any policies! He just wants to "get America working again." But how would he do that? The most concrete thing he says is that he'd pull back a lot of regulations and put us on a path to "energy independence." (Of course, every president and presidential candidate says we need "energy independence," and it never happens.)

8:54 - Santorum asks how many people in the audience want a national sales tax. Almost no one raises their hand, and Santorum tells Cain that shows how many votes he'll get. Santorum asks how many people think Congress will keep the sales tax at 9%, and no one appears to raise their hand. But Cain promised us in an earlier debate that there's no chance the taxes would ever go up!

8:58 - Up next: the candidates will ask each other questions.

9:06 - Bachmann uses her question to Perry to point out that he worked for Al Gore's first presidential campaign during the end of the Reagan administration.

9:09 - Cain asks Romney a question: Cain's 9/9/9 plan is "simple" and "neutral" (whatever that means). Is Romney's "59-point plan" simple and neutral, and can he list all 59 points? This is actually a softball question, since it gives Romney an opportunity to list the highlights of his plan. No one would expect him to list all 59 points in a debate, so the question about whether he can list them all is a red herring.

9:11 - Romney: "I'm not worried about rich people. They're doing just fine. The poor have a safety net." He's worried about the people in the middle, and that's why his tax plan is directed toward them. Good.

9:12 - Huntsman asks Romney a question. Is that the third question in a row that's gone to Romney?

9:15 - Paul asks Cain whether he stands by his past statements against auditing the Federal Reserve. Paul says Cain said people who want to audit the Federal Reserve are "ignorant." Cain adamantly says this is a misquote, that he didn't call anyone ignorant, and that Paul shouldn't believe everything he sees on the internet. Cain adds that his priority isn't auditing the Federal Reserve — it's "9/9/9"!

9:17 - Perry asks Romney a question about his health-care reform in Massachusetts. That seems like a waste of his question. Oh, the health-care issue may be bad for Romney, but Perry has to know that Romney is going to smoothly give his standard answer on health care. Perry cuts into Romney's answer, and Romney sharply says: "I'm still speaking!" Romney criticizes the high percentage of people without health insurance in Texas.

9:18 - The candidates are supposed to ask questions in alphabetical order, so Santorum declines when moderator Charlie Rose prompts him to ask a question. Santorum points out that Romney is before him in the alphabet. Romney: "You'd think someone from PBS would know that."

9:21 - Santorum points out that 4 of the candidates — Cain, Romney, Perry, and Huntsman — "naively" supported TARP. He asks Cain why voters should trust him to protect liberty given his inexperience. I believe this is the first time anyone in any of the debates has called out Cain's total lack of political experience.

9:32 - Cain is asked who his favorite Chairman of the Federal Reserve is, and he says Alan Greenspan. Ron Paul: "Spoken like a true insider! Alan Greenspan was a disaster!" Yet Paul says Greenspan agrees with him about the need to bring back the gold standard.

9:40 - Charlie Rose asks Gingrich if owning a home is no longer "the American dream." Gingrich predictably attacks this idea: some people would like America to "decay so that government could share in the misery."

9:45 - Santorum says the way to reduce poverty is to "encourage marriage," because the poverty rate among families led by a working "husband and wife" is only 5%, in contrast with the 30% poverty rate of families with just one working parent. If that's Santorum's approach, shouldn't he be interested in the poverty rate among families with two husbands, or two wives?

9:47 - Each of the candidates is asked how their personal experience would influence them as president. Cain: "I was po' before I was poor."

9:50 - Santorum says there's more upward economic mobility in Europe than in America. That seems like an odd tack for a conservative to take.

9:52 - The debate is over. Charlie Rose thanks the candidates for sitting with him at the table, and adds: "I believe in tables."

This debate reinforced Cain's newfound frontrunner status, in that the moderators and other candidates spent so much time attacking him. Whether his defenses were convincing on the merits is a matter of opinion, but as far as his presentation, he seemed unflappable, resolute, and passionate. Beyond that, I have a hard time seeing this debate changing much. Frankly, unless someone makes a huge gaffe or gives as bad a performance as Perry did last time, I doubt any of the upcoming primary debates from now until January will change much either. This cast of characters has gotten pretty familiar.

UPDATE (the next day): My mom, Ann Althouse, had a very different reaction to Cain than I did. In this post, she describes "[t]he point in the debate when my doubts about Herman Cain suddenly spiked." After a rigorous analysis of Cain's statements from last night's debate, she concludes:

Come on, people. This infatuation with Herman Cain is embarrassing. Wake up!

Monday, October 10, 2011

Still trying to make sense of the Elizabeth Warren quote about successful businesses and taxes

I've already blogged about how I don't see how the phenomenally popular quote by Elizabeth Warren about business, government, and taxes makes sense.

If you're not familiar with the quote, I recommend reading it in my older blog post before reading the rest of this post. The gist is that since a successful businessperson was only able to achieve all their success thanks to government services, they should "pay forward" — that is, pay taxes in the future.

To be clear, I do agree that businesses and the rich should pay taxes. I even agree that the rich should pay a higher proportion of their income in taxes than other people. But I take issue with the idea that by observing that the rich have benefited from government services, you've somehow made an argument for left/liberal economic policies, as opposed to any other economic policies — centrist, conservative, libertarian, whatever.

Along the same lines, Alex Knepper says:

Taxes must exist for something, of course — and it seems that the best examples of successful government programs that Warren can come up with are the left’s typical trifecta of examples — schools, roads, and law enforcement. Again for the sake of argument, let’s agree with her that these are shining examples of money well-spent — and that because of this, they merit even more spending. Her point still goes nowhere: these projects don’t actually cost all that much money. The majority of federal money (and we will consider federal spending here, since Warren is running to be a senator) is spent on entitlement programs, national defense, homeland security, and health care. Education and infrastructure don’t account for a lot. If schools and infrastructure are what Warren thinks that businessmen have to be grateful for, then they still are left with many legitimate gripes about their money being misspent.But let's look at two liberal editorials that endorse Warren's statement at length, and see if they shed any light on this.

First, the Editors of the New Republic have a piece called a "moral defense" of taxes. TNR writes:

Nobody questions whether society can require people to serve on a jury or, in times of war, to enlist in the military. So why do we question whether society can require people to pay for the government whose services, and protection, they enjoy?Before I go into the merits of TNR's editorial, I have to point out that the Editors are making a statement that's simply false. The military draft is wildly unpopular. It hasn't been used in America since the Vietnam War, when it was considered an outrage. The draft is so unpopular that even a staunch conservative like Jonah Goldberg says (as I've blogged):

I have a problem with compulsory military service if compulsory military service isn't needed at a time of war. . . . You know, the draft is a bad thing. . . . The draft is . . . an incredible . . . it is very comparable to slavery. And in some ways, it's worse than slavery, insofar as you're forcing people to kill other people and be killed. Now, it's an evil, but it's a necessary evil sometimes.By contrast, almost no one opposes taxation itself. Michele Bachmann had to admit as much in the last presidential debate, even after making this forceful statement:

You should get to keep every dollar that you earn. That's your money; that's not the government's money. That's the whole point. Barack Obama seems to think that when we earn money, it belongs to him and we're lucky just to keep a little bit of it. I don't think that at all. I think when people make money, it's their money.After all that, she gave this obligatory clarification:

Obviously, we have to give money back to the government so that we can run the government.In other words, even someone who comes across as vehemently anti-tax has to concede that we need to have some taxes in order to keep the government running (with the negligible exception of anarchists).

The basic services Warren was describing (roads, police, courts to enforce contracts, etc.) require very little taxation relative to the status quo. So, even if we only had taxation necessary to provide all those services, almost no one would be complaining that taxes are too high. (Even fairly extreme libertarians want government to be small, not nonexistent.) By contrast, most people find military conscription disturbing and abhorrent — only to be used in dire circumstances.

Onto the merits of TNR's editorial. The Editors say:

The moral case for taxation rests on two separate, but related, principles. The first is distributional. History teaches us that capitalism is an excellent economic system for generating wealth. But history also teaches us that capitalism will create losers as well as winners, often because of forces beyond any individual’s control. . . . [P]overty, like affluence, becomes its own sort of inheritance.Now, the observation about public education doesn't even make an obvious case for taxing people at a level sufficient to pay for public schools. While I'm sure many rich businesspersons did attend public school, it remains an open question how much to emphasize public as opposed to private schools. If some of those rich people attribute their success to public education, they can go ahead and make that argument — fine. But other rich people might feel they would have been at least as successful if they had attended private schools. Still other rich people might say their private education shows that we should be focusing more on private schools. (I realize that you might not care much about what kind of education allows 1% of the population to become rich — but I'm operating under Warren's own premise that we should shape policy based on looking at what has benefited the rich.)

A civilized society recognizes this problem and vows to mitigate it. If capitalism does not offer everybody at least some realistic hope of upward mobility, it cannot survive. Here in the United States, a part of our solution has been to enact government programs that offer the needy minimal allotments of sustenance (food stamps) and shelter (housing choice vouchers), that provide the less affluent with cash (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) and college tuition (Pell Grants), and that guarantee all citizens pensions (Social Security) and health insurance (Medicare, Medicaid, and the Affordable Care Act). These programs cost money. And the money has to come from somewhere.

The second reason we need taxes isn’t about the least fortunate; it’s about public goods. You’ll frequently hear conservatives argue that taking money from people, particularly successful people, is unfair because they, not the government, earned that money. But that’s not quite right, for reasons Warren explained very well in her monologue. Behind every successful individual is a set of public investments that past generations made. Could Bill Gates have made his fortune without government-financed education and technology? Could Sam Walton’s stores have spread across the country without government-sponsored roads on which goods and customers travel? . . .

The importance of public goods is not simply an argument for progressive taxation—that is, asking people who’ve been extremely successful to support things like roads and education, from which they and their businesses benefit. It’s also an argument for taxation in general. The rich should pay more, yes, but everybody who can pay something toward the cost of financing government should do so.

As for TNR's support of progressive taxation, I still don't see how that follows from all this discussion of how someone who runs a profitable factory couldn't have done it without police to stop the factory from being burgled or their employees from being murdered! Whether revenues should come from progressive or flat taxes — or, high or low corporate taxes — are separate issues from the observations about the successful factory. The New Republic's Editors believe that the tax rates should be progressive, and they may be exactly right about that. As I said, I happen to agree with them. But this isn't the same issue as whether to raise enough tax revenues to fund the police and courts.

By the same token, I happen to agree with TNR that government should provide some safety net for our least fortunate citizens. But I don't think even the editorial itself is arguing that this is explained by Warren's discussion of a businessperson who enjoys public services like the police to keep their factory safe.

It's also worth stepping back and asking what people like Warren and TNR are trying to accomplish from all this. The undertone of their statements is that conservatives might become more liberal if only they'd think more clearly about the importance of government in a capitalist society (especially the federal government, since Warren is running for the U.S. Senate). Hence, TNR claims to be making a "moral case" against conservatives who "argue that taking money from people, particularly successful people, is unfair because they, not the government, earned that money."

But just look back at Michele Bachmann's statement during the debate. The conservatives who say this kind of thing certainly are upset about taxes — but not all taxes. They want people (including the rich, of course) to be taxed enough to raise money for the things they like, including the police and the military. For many conservatives, this even includes public schools and Social Security and Medicare. At the same time, they would like to see massive federal tax cuts, because they believe the federal government wastes a lot of money on programs that either do more harm than good, or might even do a little good but not enough to be worth all the money they cost. These conservatives may be right or wrong, but I don't think their mistake is in how they think about the very nature of taxation itself. Everyone is for taxation — to pay for the things they like. And everyone is opposed to taxation — when it pays for things they don't like.

Now, onto the other editorial I mentioned: E.J. Dionne wrote this bizarre piece. I have less to say about this one, because almost none of it is spent actually making the case for what Warren said. 90% of it consists of Dionne (gleefully?) taking jabs at his Washington Post colleague George Will for writing a poorly reasoned editorial against Warren. (Dionne is right about that: Will's column was weak.)

When Dionne finally gets around to making the "proper case for liberalism" — which he interestingly admits "does not happen enough" — here's all he says:

Liberals believe that the wealthy should pay more in taxes than “the rest of us” because the well-off have benefited the most from our social arrangements. This has nothing to do with treating citizens as if they were cows incapable of self-government. As for the regulatory state, our free and fully competent citizens have long endorsed a role for government in protecting consumers from dangerous products, including tainted beef.As I said in my earlier blog post, even if you agree with this, you're in agreement with some people who are pretty far right. Even supporters of a flat income tax agree that the wealthy should pay more in taxes than the rest of us. Of course, he would probably say: "No, that's not what I meant! I mean the rich should pay a higher percentage of their income." I happen to agree, but not necessarily because "the well-off have benefited the most from our social arrangements." I'm for progressive taxation because we need to get the revenue from somewhere, and while taxing anyone is going to cause pain, it'll hurt the rich the least because they have more money to spare. If this means I end up agreeing with Dionne or Warren on that issue, I'm fine with that. But even if this policy, or other left-leaning policies, are good ideas, I don't know see how Warren or Dionne or The New Republic have given the real reasons why they're good ideas.

If conservative voters are angry with the Republican establishment, why is Mitt Romney winning?

Ramesh Ponnuru says: "Make a mental list of the last four Republican nominees -- George H.W. Bush, Bob Dole, George W. Bush and John McCain -- and the notion of a Romney victory in the primaries becomes less surprising."

Sunday, October 9, 2011

"Stop Blaming Wall Street"

This long and dense article by John Judis gives a history of how the United States' economic and monetary policy has increasingly marginalized the manufacturing industry.

The whole thing is worth reading, and the history is so complicated that I wouldn't even try to sum it up. But here's the bottom line (notice that Judis is criticizing liberals here even though he's pretty liberal himself):

Conservatives blame “big government” for throttling entrepreneurship; liberals tend to take aim at Wall Street. Rolling Stone writer Matt Taibbi memorably described Goldman Sachs as “a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money.” Among less inventive critics, the term in vogue is “financialization.” According to author Kevin Phillips, who popularized this notion, financialization is “a process whereby financial services, broadly construed, take over the dominant economic, cultural and political role in a national economy.” . . .

One thing is clear: Financialization, in some form, has taken place. In 1947, manufacturing accounted for 25.6 percent of GDP, while finance (including insurance and real estate) made up only 10.4 percent. By 2009, manufacturing accounted for 11.2 percent and finance had risen to 21.5 percent—an almost exact reversal, which was reflected in a rise in financial-sector employment and a drop in manufacturing jobs. It is also clear that high-risk speculation and fraud in the financial sector contributed to the depth of the Great Recession. But Phillips, Johnson, and the others go one step further: They claim that financialization is the overriding cause of the recent slump and a deeper economic decline. This notion is as oversimplified, and almost as misleading, as the conservative attack on the evils of big government. . . .

Some critics of financialization have insisted that breaking up the banks is the key to reviving the U.S. economy. Charles Munger, the vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, has said, “We would be better off if we downsized the whole financial sector by about eighty percent.” It’s certainly true that, if the derivatives market isn’t thoroughly regulated and if reserve requirements for banks aren’t raised, then a very similar crash could happen again. The Dodd-Frank bill goes part of the way toward accomplishing this, though it leaves too much to the discretion of the Treasury, the Federal Reserve, and regulatory agencies.

But, unless the United States takes the necessary measures to revive its industrial economy, radical downsizing of the financial sector could do more harm than good. It could even deprive the economy of an important source of jobs and income. Many mid- and large-sized cities—including New York, San Francisco, Jacksonville, Charlotte, Boston, Chicago, and Minneapolis—are now dependent on financial services for their tax bases. Instead of agitating for breaking up the banks, critics of financialization would do well to make sure that Republicans don’t gut Dodd-Frank.

Why, then, has financialization played such a starring role in explanations of America’s economic ills? One obvious reason is that the financial crash did turn what would have been an ugly recession into a “great” recession. This sequence of events is an almost exact replay of the Depression, which began with a short recession in 1926 . . . . In both cases, the financial crash played the most visible role.

Another reason is the centuries-old tendency in American politics to allow moral condemnation to outweigh sober economic analysis. Picturing bankers and Wall Street as a “parasite class” or as “vampires” is an old tradition in American politics. It goes back to Andrew Jackson’s war against the Second Bank of the United States and to Populist Party polemics against “a government of Wall Street, by Wall Street, and for Wall Street.” And currently it is one of the few ideological bonds between the Tea Party and left-wing Democratic activists. But, just as free silver wasn’t the answer to the depression of the 1890s, smashing the banks isn’t the answer to the Great Recession of the 2000s. The answer ultimately lies in the ability of U.S. businesses to produce goods and services that can compete effectively at home and on the world market.

Saturday, October 8, 2011

Friday, October 7, 2011

Cain leaves everyone else in the dust in the latest Zogby poll.

I don't put much stock in national polls as a predictor of who will win the primaries, since the real primaries and caucuses are done state by state, giving certain states a huge amount of power and making others irrelevant to the outcome.

But national polls can still show an overall trend in a candidate's popularity, and the latest Zogby poll is amazing: Herman Cain is the frontrunner by a 20% margin. I almost did a double take to make sure 20% didn't refer to the total support for Cain. No, that's how much more support he has than the second-place candidate, Mitt Romney.

Cain has 38%. Romney has 18%, which is as much as he's gotten in any Zogby poll.

Rick Perry? Just 12% — less than a third of Cain, and tied with Ron Paul. Each of the other 5 candidates has less than 5%.

Uncannily, the Cain/Perry divide was almost exactly flipped in Zogby's poll on September 12: Perry 37%, Cain 12%. (The second of Perry's 3 debates happened on the evening of September 12, and he hadn't yet given his worst debate performance yet.)

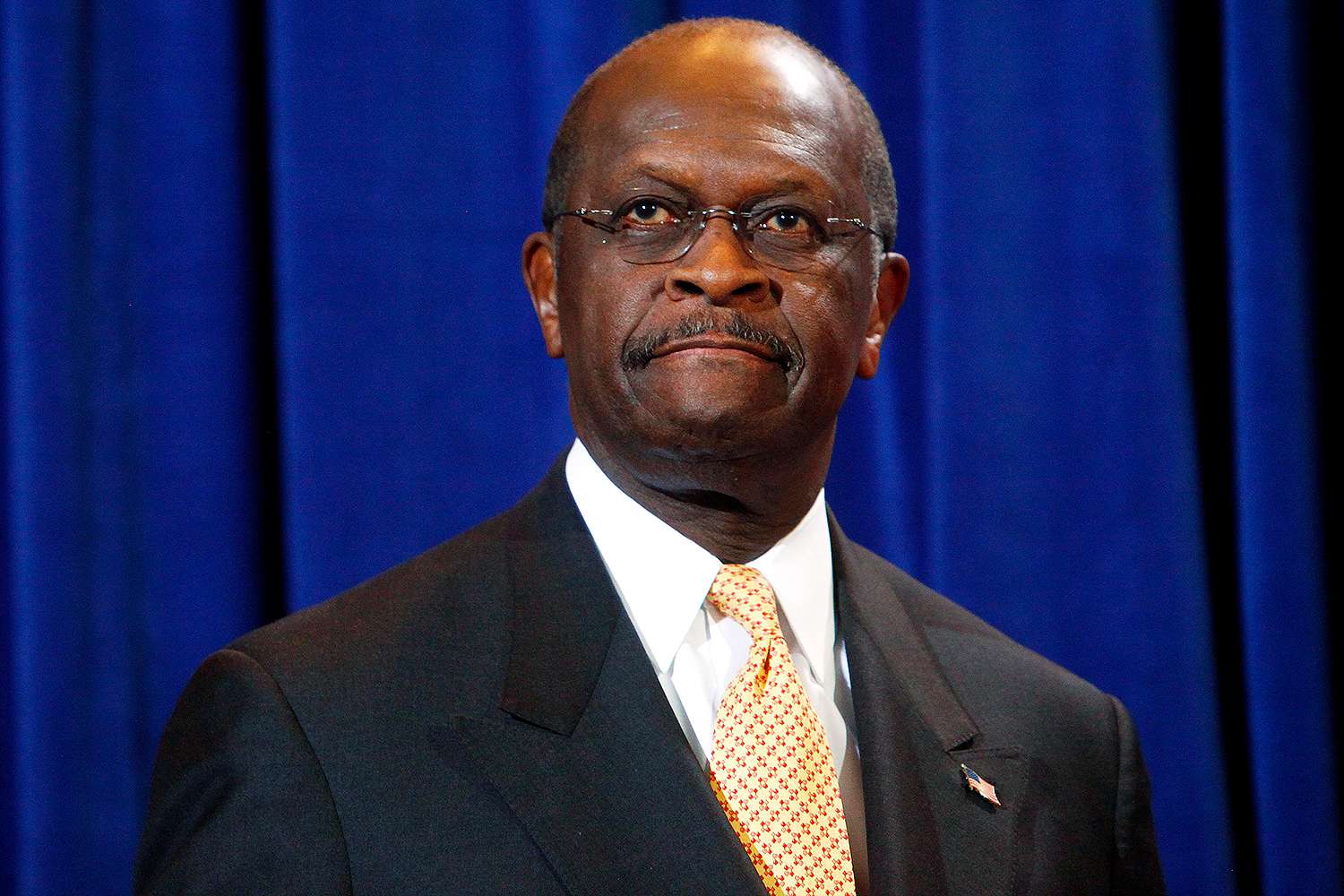

Herman Cain on America's racial progress

From the Washington Post's profile on Herman Cain:

In his book, Cain writes that, as a child, he was forced to sit in the “colored” section of the bus, and while in graduate school in Indiana he found it so difficult to find a barber who would cut black hair that he bought clippers and cut his own — a practice he holds onto today.

He tells of a time when he and his brother sneaked a taste of the “whites only” water fountain. “Then we looked at each other and said, ‘You know what? The ‘whites only’ water tastes just the same as the ‘coloreds’ does!’ ”

Asked recently on Fox News why he’s not more bitter about his treatment under segregation, Cain answered with an optimistic spin.

“I’m not angry with America, because America has something that a lot of other countries don’t have: The ability to change,” he responded. “That’s the greatness of this country. We have always had struggles throughout our short 235-year history. Why be bitter? Why not embrace the change, especially since it’s positive?”

(Photo by Eric Thayer/Getty.)

"[T]o the extent that racial preference fans at Berkeley condemn opposition to their ideas as offensive — i.e. blasphemous — . . .

. . . and leave temperate-minded people afraid to speak their minds, they have become, themselves, The Power—a kind of power that good people are responsible for Speaking Truth To." — John McWhorter

Thursday, October 6, 2011

Jon Huntsman finally wins a straw poll.

The results are in from the straw poll conducted at the Take Back The American Dream conference this week . . . .TPM notes that his victory among liberals is either "very good" or "very, very bad" for Huntsman.

An overwhelming 49% of [337] straw poll voters at the progressive conference said Huntsman is the Republican “most qualified to be president” from a field of 11 that included the not-running Sarah Palin, the not-running Chris Christie and the still-kind-of-thinking-about-it Rudy Giuliani.

Policy uncertainty and jobs

"Policy uncertainty" has dramatically increased since the September 2008 crash. (via)

That article (written by 3 economists at Stanford and University of Chicago) notes that it's hard to disentangle uncertainty about policy (tax rates, health-care law, regulations) from uncertainty about the economy as a whole. But the authors tried to isolate policy uncertainty as a distinct factor inhibiting businesses from hiring people.

They "estimate that restoring 2006 levels of policy uncertainty would yield an additional 2.5 million jobs over 18 months."

UPDATE: My mom, Ann Althouse, remarks: "And yet the government is always scrambling to help us out with new policies." She quotes President Obama from today:

“If Congress does nothing, then it’s not a matter of me running against them. I think the American people will run them out of town. I would love nothing more than to see Congress act so aggressively that I can’t campaign against them as a do-nothing Congress.”She urges us to "[r]econsider the amazing value of nothing."

Wednesday, October 5, 2011

Steve Jobs has died at 56.

Steve Jobs died today due to pancreatic cancer, just over a month after he resigned as CEO of Apple.

The Apple.com homepage is now a tribute to Jobs.

The first sentence of the New York Times' obituary:

Steven P. Jobs, the visionary co-founder of Apple who helped usher in the era of personal computers and then led a cultural transformation in the way music, movies and mobile communications were experienced in the digital age, died Wednesday.In any obituary thread on Metafilter, people normally post a period to represent a moment of silence for someone who has died. Many commenters today are posting an Apple logo instead. (You'll only see them if you're using a Mac.)

Searching through the Metafilter thread shows that several different commenters have used the word "aesthetic." For example, this comment:

Thank you for all the pretty computers. Meaning, thank you for thinking about design and style and what the rest of us out here had to look at and touch every day. Apple has forced the rest of the industry to think just a little bit more about the aesthetic of the consumer experience, which I appreciate.Many comments also use the word "beautiful":

Steve Jobs believed the revolutionary idea that the tools you use should be as beautiful as the work you produce with them.The New York Times quotes a Twitter post:

RIP Steve Jobs. You touched an ugly world of technology and made it beautiful.A few years ago I was having a conversation about computers with an acquaintance who seemed to know more about them than I did. I had made it clear that I was a lifelong Mac user (with one small exception). He tried to explain why he preferred PCs to Macs. He said something along the lines of: "All Apple does is give computer users exactly what they want." Amazingly, he meant that as a criticism of Macs — for being too user-friendly and appealing. My response: "Gee, if that's all Apple does, isn't that enough?"

As I mentioned, there was only one exception to my lifelong devotion to Macs. In my first semester of law school, I had to use a PC. In order to take an exam on your computer you had to use the specific exam-taking software provided by the school, and it wasn't Mac-compatible. (Handwritten exams are allowed, but that isn't a viable option since you don't get any extra time.) At the beginning of the next semester, my law school announced that the software had been updated to be Mac-compatible. I was so frustrated by my bad luck — I can't get a new computer when I just bought a computer 4 months ago that's working fine, can I? Of course, as a first-year law student, I wasn't earning any money. I apologetically asked my mom if she could pay for a new Macbook for me, saying "I know I just got a computer . . ." but starting to explain why I thought the Mac's improvement over the PC would be worth it. She cut me off, saying: "I know exactly what you mean. You don't even need to explain it." (I got the Mac and sold the PC to another student — which wasn't hard, since I had the perfect explanation of why I wanted to sell a perfectly good computer.)

If you're a Mac user, you might not be able to put into words why using a Mac is so important. You just know.

The New York Times quotes Jobs:

He put much stock in the notion of “taste,” a word he used frequently. It was a sensibility that shone in products that looked like works of art and delighted users. Great products, he said, were a triumph of taste, of “trying to expose yourself to the best things humans have done and then trying to bring those things into what you are doing.”The New York Times adds:

As the gravity of his illness became known, and particularly after he announced he was stepping down, he was increasingly hailed for his genius and true achievement: his ability to blend product design and business market innovation by integrating consumer-oriented software, microelectronic components, industrial design and new business strategies in a way that has not been matched.A commenter in the Metafilter thread says:

I just told my wife, who is completely disconnected from the geek world where I live, that Steve Jobs was dead.As I recently blogged and as many people are quoting today, Jobs had this to say about life and death in his commencement address to Stanford University in 2005:

When I told her, she accidentally dropped her iPad 2 on the hard floor but it did not break. It didn't have a scratch on it.

I think that says something about this man who demanded and delivered excellence.

No one wants to die. Even people who want to go to heaven don't want to die to get there. And yet death is the destination we all share. No one has ever escaped it. And that is as it should be, because Death is very likely the single best invention of Life. It is Life's change agent. It clears out the old to make way for the new. Right now the new is you, but someday not too long from now, you will gradually become the old and be cleared away. Sorry to be so dramatic, but it is quite true.

Your time is limited, so don't waste it living someone else's life. Don't be trapped by dogma — which is living with the results of other people's thinking. Don't let the noise of others' opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become.

(Photo from this website via Google image search.)

Tuesday, October 4, 2011

The problem with books, according to Sam Harris

First of all: they're too long. Harris explains:

I love physical books as much as anyone. And when I really want to get a book into my brain, I now purchase both the hardcover and electronic editions. From the point of view of the publishing industry, I am the perfect customer. This also makes me a very important canary in the coal mine—and I’m here to report that I’ve begun to feel woozy. For instance, I’ve started to think that most books are too long, and I now hesitate before buying the next big one. When shopping for books, I’ve suddenly become acutely sensitive to the opportunity costs of reading any one of them. If your book is 600-pages-long, you are demanding more of my time than I feel free to give. And if I could accomplish the same change in my view of the world by reading a 60-page version of your argument, why didn’t you just publish a book this length instead?Did Harris find my blog post called "6 ways blogs are better than books," specifically #1 and #6, and steal my idea (which I, of course, took from other people)? Probably not. Most readers have had the same realization. The question is who has the courage to publicly admit it, and act on it.

The honest answer to this last question should disappoint everyone: Publishers can’t charge enough money for 60-page books to survive; thus, writers can’t make a living by writing them. But readers are beginning to feel that this shouldn’t be their problem. Worse, many readers believe that they can just jump on YouTube and watch the author speak at a conference, or skim his blog, and they will have absorbed most of what he has to say on a given subject. In some cases this is true and suggests an enduring problem for the business of publishing. In other cases it clearly isn’t true and suggests an enduring problem for our intellectual life. . . .

[W]riters and public intellectuals must find a way to get paid for what they do—and the opportunities to do this are changing quickly. My current solution is to write longer books for a traditional press and publish short ebooks myself on Amazon. If anyone has any better ideas, please publish them somewhere—perhaps on a blog—and then send me a link. And I hope you get paid.

I'm currently reading a book that has done both: Tyler Cowen's The Great Stagnation: How America Ate All The Low-Hanging Fruit of Modern History, Got Sick, and Will (Eventually) Feel Better. It was originally released exclusively as an eBook, and was later released as a dead-tree book. One of the blurbs is by Matthew Yglesias, calling it "a great innovation in current affairs publishing — much shorter and cheaper than a conventional book in a way that actually leaves you wanting to read more once you finish it."

In the book's introduction, Cowen makes an odd argument for his decision to release it in exclusively digital form:

I meant for [the ebook version] to reflect an argument from the book itself: The contemporary world has plenty of innovations, but most of them do not much benefit the average household. (2)So, publishing it as a digital book only (until it became so successful that the dead-tree version was a no-brainer) made sense because it didn't help many people! OK. That argument is even more innovative than the book's short length.

But then Cowen realized that eschewing paper was a problem. He writes:

Some readers . . . were frustrated with the Digital Rights Management systems embedded in nearly all published electronic content. These systems mean that you can't pass around an eBook like a paper book. Libraries don't necessarily own eBooks forever; it's possible for the publisher to flip the switch and literally take them back — debate on this topic is raging. Paper books are easier to give as gifts and easier (sometimes) to use in the classroom. On top of all that, Amazon.com, B&N.com [Don't try typing that into your browser. He meant bn.com. — JAC], the iBookstore, and related services do not yet reach into every corner of the globe. Paper books can get to remote places a little more reliably. Personally I like reading books on trips and dropping them somewhere creative, in the hope they will be picked up by a surprised and delighted future reader. (2-3)I'm convinced by those and other reasons to keep paper books around for good. So I hope Sam Harris is wrong to say that "[t]he future of the written word is (mostly or entirely) digital." I see little reason why authors and publishers can't heed Harris's advice to make books shorter while still publishing paper books. Harris says readers won't be willing to pay for a 60-page book. Well, I paid for Cowen's book, which is 109 pages. It's just 89 pages without the endnotes and index. I think Harris is underestimating people's willingness to buy a reasonably priced, well-supported nonfiction book that gets to the point in 100 pages, as opposed to a 300- or 400-page book that might be even more rigorously supported but also includes more repetition — and will be much less likely to be read in its entirety. As my mom, Ann Althouse, more succinctly put it in her message to writers (particularly one writer who scolded her for not reading every word of her book):

You pad. I skim.IN THE COMMENTS: My dad, Richard Lawrence Cohen, says:

I don't follow Harris' argument about pricing. Long books are the pricing problem, because they cost much more to print and readers are reluctant to pay an equivalent percent extra to make up for it; thus the tendency of long books to have small, light print and thin paper. Meanwhile, if a book is only 100 pages, you can still charge almost as much as for a 150-page book and save a lot of the printing costs. The relatively higher price on the short book creates perceived value in the reader's mind, justifying the expense. We're all accustomed to paying $15 for a paperback anyway, and page-counting isn't a top priority; the page range consumers accept at that price is pretty wide. It's a mistake to assume that the reader is glad to have more pages for the money; the extra pages are a chore. It's a welcome relief to be able to get the message fast.

Rick Perry is in "free fall."

So says TalkingPointsMemo, reporting on a new poll from Florida:

Perry dropped from being tied with Romney at 25 percent apiece in a pre-debate poll from the same firm ten days ago to having 9 percent support from the the Florida GOP. [Mitt] Romney moved up slightly and [Herman] Cain essentially took support from Perry on his way to second place.Here are the poll results, from a sample of "likely voters":

Romney 28%, Cain 24, [Newt] Gingrich 10, Perry 9Wow.

And Perry was going out of his way to court Florida:

On the morning of the [Florida straw poll] vote, Perry shook hundreds of hands, signed autographs, posed for pictures, and made small-talk with the delegates. He also met privately with party leaders, elected officials and key activists. He spent lavishly to woo the straw-vote electorate—including a large buffet breakfast spread on Saturday morning offered gratis to every delegate.

Monday, October 3, 2011

America needs to have so much more shopping . . .

. . . that we're resorting to imported shoppers.

Do you "love your iPhone"?

"Literally"?

Or, is an article that says modern technology is disconnecting us from human interaction, and claims to back this up with a brain imaging study, too good for the New York Times to check?

Sunday, October 2, 2011

Newt Gingrich calls same-sex marriage "temporary."

Gingrich says:

“I believe that marriage is between a man and woman. . . . It has been for all of recorded history and I think this is a temporary aberration that will dissipate."A headline on TalkingPointsMemo gives the obvious response:

Just Like His Own Marriages

And here's a recent Bizarro comic:

Saturday, October 1, 2011

How bad is it to cherry-pick scientific studies that support your position?

Very bad, explains Ben Goldacre. He calls out Aric Sigman, a popular science writer who admitted to cherry-picking only the studies that supported his pre-existing views about day care (that it's harmful to young children).

At the end of his post, which is worth reading in its entirety, Goldacre concludes:

A deliberately incomplete view of the literature, as I hope I’ve explained, isn’t a neutral or marginal failure. It is exactly as bad as a deliberately flawed experiment, and to present it to readers without warning is bizarre.I have a feeling that last sentence was carefully edited, and that he originally wrote a different word than "bizarre."